American Horror Remake: The Ring

"I've seen footage" - Death Grips

In 2002, Gore Verbinski and DreamWorks released their remake of Hideo Nakata's Ringu, now titled, The Ring. For being kids who were not yet ready for the world of more underground avant-garde horror, and being too early for the era of "elevated horror" (jury is still out on that term as a genre) this was the "I bet this one will scare you" of movie recommendations amongst friends. Waking up to the glitching DVD menu screen that looped endlessly because we were too lazy to turn the TV off at two in the morning is still a core memory to this day, and confirms the intent of the film's haunting analog-glitch imagery lingering in the mind.

On 9/11/2001, a year before the film's release, classrooms across the US were placed on lockdown with the CRT TV carts rolled out to run major network coverage of the attacks. All at once, American children were introduced for what may have been their first experience with a profound moment of mass murder caught on video. That same footage was seen on repeat for the entire day, then the rest of the week, and then what felt like the entire year, with new angles of the attack being shown the second they were cleared for air at major and local networks. The footage attached itself to the viewer and introduced America's fractured geopolitical affairs to younger millennials for the first time in their lives.

Footage of the attacks have been reviewed, dissected, and memed to death in the years following to the degree that it plays like a syndicated sitcom at this point. We can all collectively recall the angles, the faces, and the reactions to those captured moments. It wasn't an event that allowed someone who only witnessed it on television time to process what had just happened. Even if you were off-grid that day, any screen you happened to come into contact with in the days following seared the images onto your brain. Desensitization can be tough to admit, but it is inevitable. Nobody ever forgets their first raw footage of death caught on camera. We were now apart of American media's audience, whether we liked it, or even fully understood it.

It was around the same time these same younger millennials started to become curious about the internet and explore online with friends. Those around today who are unfazed by a major social media's algorithm descending into slop were once spending the night at their friend's house on websites like eBaum's World, Omegle, and Something Awful. Tough as you claimed to be, you eventually saw something you couldn't quite shake. Imagery that ranged from gross-out contests triggering a simple gag reflex to victims of a botched execution kept alive as a depraved joke for the audience to witness true organic suffering. It was a time before moderation teams could remove content that violated community guidelines, and it was a time before you could find a career politician and a genuine sociopath with an incriminating hard drive on the same website owned by the richest man in the world.

Our parents believed that this content was a great specter that would divert the youth away from the light of God and drive us to commit unspeakable crimes and destabilize the nation. We were all able to laugh away the fear-mongering talking heads that lacked computer literacy until the Slenderman incident proved them to be reasonably concerned, if only for that moment. Even the most steadfast libertarian who will fight censorship to their dying breath can have a Tipper Gore moment - that reactionary instinct to worry about the younger generation's flavor of media consumption, and how it might inspire subversive thinking and impure thoughts.

A poorly-behaved theater during a horror film will occasionally blurt out an instruction to the actor on screen like "Don't open that door!", "Don't go in the basement!", "Don't have premarital relations in that tent!". The Ring managed to have audiences demanding that the cast "stop sharing and viewing that media!". The film acknowledged the lurking danger of shared media that could inflect psychic damage on the viewer, just as the antagonist of The Ring, the ghost of a young girl named Samara, was able to do through her captured essence in the infamous VHS tape. There's a scene in the film that shows Naomi Watts' character, Rachel, coming home to find that her adolescent son has just finished watching the cursed footage. This is the core of reactionary parenting come alive - being unable to protect your children from the harmful media.

While Verbinski's remake was never an explicit political statement, the film rolls in on a legacy concern of reactionary pro-censorship conservatives in it's opening scene. The start of the film opens on two teenage girls channel surfing at home one night during a thunderstorm, still wearing their prep school uniforms. One of the girls, Becca, mentions an urban legend of a cursed videotape that contains disturbing imagery. She says that anyone who bears witness to these images is contacted via telephone immediately after viewing it, and a haunting voice informs them that they have "seven days to live". Later that evening, Becca's friend, Katie, is murdered and disfigured by an unseen force.

Now, as we all formally understand, hormonal-inclined and curious teenagers in horror films having their lives taken by a malevolent force for losing their innocence is only supposed to happen if you ignore a suspicious gas station manager who tells you to bail on your camping trip. In The Ring, the two teenage girls are safe at home, no drugs or alcohol present, and no boys have been invited over. In this universe, Jason remains in the lake, Michael is still locked in the asylum, but the teenage girl is unable to escape the cursed footage. Katie even states that she first saw the film at a cabin with her boyfriend, which is a classical horror setting if there ever was one. Instead of falling victim to a familiar knife, hatchet, or chainsaw, Katie was a victim of footage.

After her death, Katie's mother enlists the help of her sister Rachel (Naomi Watts) a Seattle-based journalist, to investigate Katie's horrific demise. Rachel discovers that Katie's friends who were present during the initial viewing of the tape have also died in similar circumstances. Now on the case, Rachel views the footage, and immediately gets the mysterious phone call afterwards. After, she contacts her ex Noah, a video analyst, to give him a copy of the footage to examine. Verbinski makes the choice to sub Nakata's version of Noah's character, originally a psychic, for a career analog video analyst who does not harbor any supernatural tether to the other side.

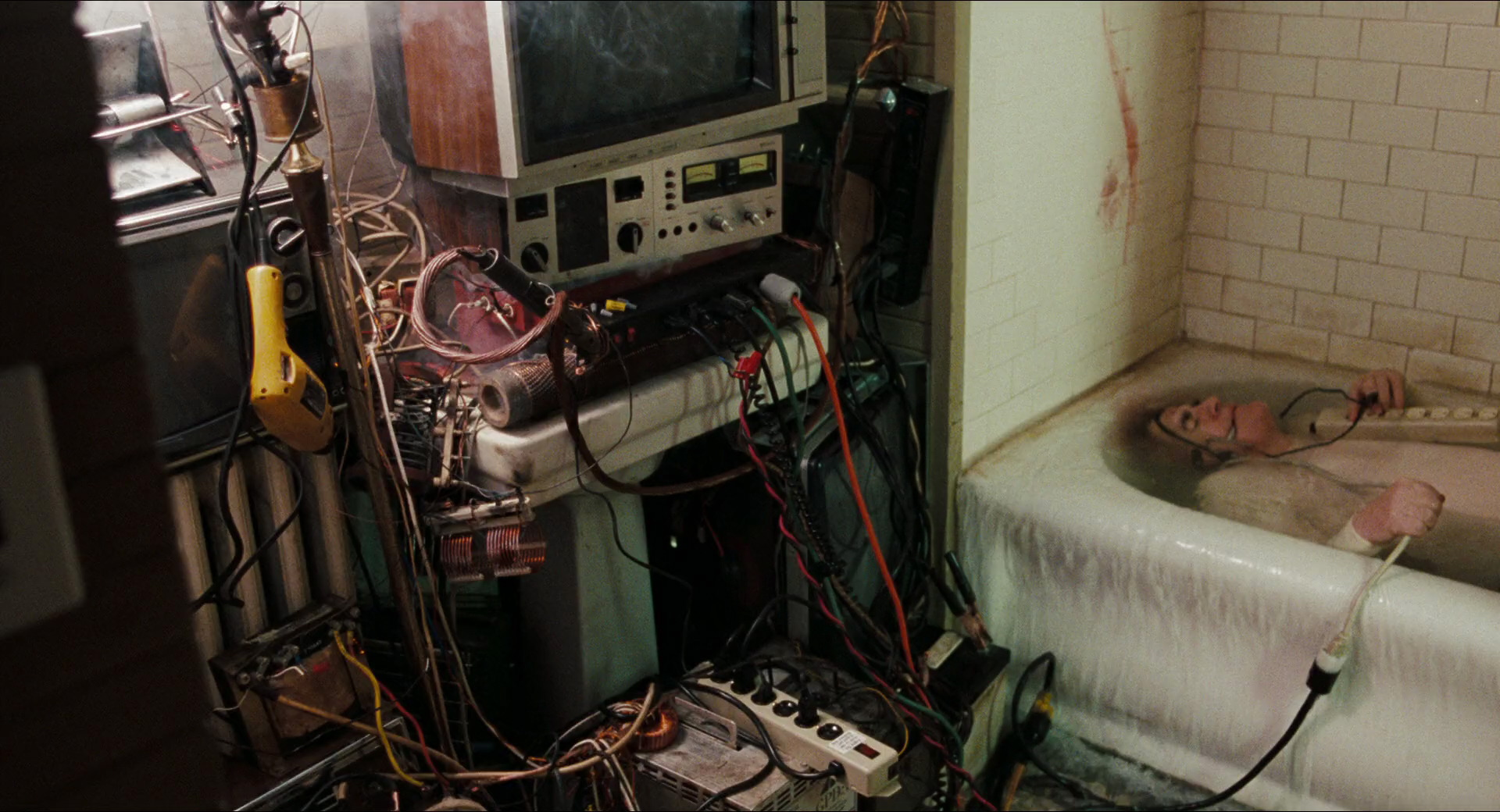

This choice always stood out when comparing the two films. While it removes an ounce of the original film's supernatural narrative, Noah is a character shown to be cemented to the film's focus on physical media. Verbinski emphasizes the cold and gray interiors of Noah's apartment, which doubles as his video engineering workspace that accentuates his connection to be with the physical instead of the metaphysical. Verbinski also features scenes of a separate broadcast station setting, in which Rachel uses analog racked AV equipment to manually stretch the cursed tape to attempt to identify clues that may point to its origin. Verbinski places focus on the characters as they work the controls and uses the clicks and static whir as accompanying audio that keeps the audience intimate with the physical analog environment. These characters are shown to interact with technology as a means of searching for truth in the static as they combat the spread of the cursed media itself.

This is further exemplified in one of the film's most chilling scenes, in which Rachel travels to Moesko Island in search of clues and meets Samara's father, Richard Morgan, played by Brian Cox. Richard is a former horse trainer who, with his now deceased wife, Anna, adopted Samara after being unable to have a child. Rachel and Noah investigate various local medical practices associated with the Morgans, and a local doctor reveals that Anna claimed that being around Samara made her mentally ill with hallucinatory visions, and caused Richard's horses to drown themselves trying to escape. Rachel pursues Richard, believing he abused and imprisoned Samara in his barn. Angry that Rachel believes him to to be the abuser, Richard is unable to cope with his daughter's legacy of psychological terror that killed his wife being forever preserved on tape. Rachel witnesses him wrap himself in electrical cords connected to a glitching television, place a horse bridle on his head, and electrocute himself in the bathtub, surrendering to the crudely assembled technology that carries his daughter's curse into the physical world.

A key to the success of The Ring is Verbinski's ominous green-gray stormy setting in the PNW. An atmosphere so thick it seems to find itself penetrating even the film's interiors. The Ring makes use of this atmosphere as a pervasive sense of dread that lingers over each character in nearly every frame. As the visions from the tape pulsate through the minds of those who have watched it, the clouds grow darker, and our characters are unable to escape their gloom even while sheltered inside. It's an experience for the audience that reminds us that the dread that we witness in media is taken inside with us. We have to digest that very media that disturbs us over the course of many days, months, and sometimes years, and its gloom seems to hang in the background as we go about our day.

The Ring never tries to pick up where David Cronenberg's 1983 film Videodrome left off with regard to its central theme, but it does offer a similar, more somber metaphor for the use of media to degrade and destroy a person's psyche. In Cronenberg's film, a sleazy UHF TV station president discovers a clandestine operation to harness prototype media technology that could be used to kill anyone who consumes violent or sexual content. Videodrome questioned if disturbing footage could corrupt and empower evil within a person, whereas The Ring reveals that the effects of potentially harmful media has already been released into the world, and acts as a cancerous scar on the human brain. The film's somber atmosphere and the characters' inability to keep up in their race against the clock speaks more to the distribution of generational doom, passed from person-to-person, in the form of a videotape.

The Ring is an American remake that was remade at a time when American children everywhere are adopting the violence of the world. The Ring has now arguably cemented itself as a faithful American adaptation that began with a firm handshake given to Hideo Nakata's J-horror hit. It's initial audience are now adults that can casually view this film after years of exploring the depths of the horror genre as far as they can stomach. They've seen the hits of the New French Extremity movement, Salò, Faces of Death, The Poughkeepsie Tapes, and A Serbian Film (sorry, had to mention it), and can talk about them openly. Their psyche no longer becomes ill upon witnessing disturbing imagery. They realize that not even a gore subreddit, or our nationwide annual replay of a terrorist attack can trigger a visceral response.