American Horror Remake: The Crazies

"The next time that somebody tells you, “the government wouldn’t do that,” oh yes they would."

Pulling off the premise of The Crazies in 1973 was a tangible reality for the king of the American zombie genre, George A. Romero. Romero shot The Crazies during a time when America's geopolitical efforts were struggling to maintain their zeal amongst the public nearing the end of the war in Vietnam. The nation was also looking down the barrel of a coming recession as the economic gains made post-WWII started to dry up, and that same faith in American economic interests was also becoming more difficult to maintain. This eroding trust began to show in our media with many films in the following years, both with subtle and not so subtle narratives, depicting criticism of the US government's involvement in Vietnam, and showing the struggling American middle-to-lower class trying to stay afloat in the unstable times that the war produced.

The plot of Romero's The Crazies depicts two firefighters, and Vietnam War veterans, plunged into sudden chaos after a downed military plane carrying a biological weapon code-named "Trixie" crashes, infecting the town's water supply. Trixie's effects are discovered to cause victims to turn rabid and homicidal. As the town deals with the terror of neighbors turning on one another, those fleeing safety run into contact with a containment team sent in by the military to stop the spread of Trixie by use of lethal force on the infected townspeople. Romero's film captured a widespread fear among American's who became critical of not only the United States' involvement in Vietnam, but their mask-off embrace of chemical warfare to gain an upper hand in the conflict.

While this premise differs from Romero's popular narrative of the dead coming back to life, which packs its own social commentary, The Crazies is more direct about having roots in some very real horrors in American history. The same year that Romero's film released, a program known as Operation Whitecoat was discontinued by the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, Maryland. The research began in 1954 and focused on identifying a dose response against infections that were suspected of potentially being used in a biological attack. The term "Whitecoats" was used as a nickname for the volunteers in the program. While these "Whitecoats" were not round up and subjugated to forced medical experimentation, these military medical operations have spurred fears and questions among the public.

In Ethical And Legal Dilemmas In Biodefense Research, Dr. Jeffrey E. Stephenson, and Dr. Arthur O. Anderson detail Operation Whitecoat as follows:

"In 1955 military research studies using human participants began in a program called CD-22 (Camp Detrick–22) that included soldier participants in a project called Operation Whitecoat. The participants were mainly conscientious objectors who were Seventh-day Adventists trained as Army medics. The program was designed to determine the extent to which humans are susceptible to infection with biological warfare agents. The soldier participants were exposed to actual diseases such as Q fever and tularemia to understand how these illnesses affected the body and to determine indices of human vulnerability that might be used to design clinical efficacy studies. In keeping with the charge in the Nuremberg Code to protect study participants, the US Army Medical Unit, under the direction of the Army surgeon general, carefully managed the project. Throughout the program’s history from 1954 to 1973, no fatalities or long term injuries occurred among Operation Whitecoat volunteers."

The narrative of citizens falling victim to their government's desire to further develop their military industrial complex's capabilities and test those capabilites on unwitting test subjects has been a hallmark of American horror and science-fiction for generations. The pilot episode The Twilight Zone features an American test pilot succumbing to madness in a simulated town void of all people to test the effects of isolation on an individual's mental fortitude. The X-files mixed anti-government conspiracy culture with a charming workplace romance that had us rooting for two FBI agents who were always stepping into their own government's deep operations and cover-ups. These different versions of this narrative are nods to some very real conspiracies that revealed atrocities committed by governments around the world to reduce blowback for their mistakes in conducting operations similar to that of Operation Whitecoat, but without the "willing participant" part of the operation.

Breck Eisner's The Crazies happened to slip into theaters in the middle of 24 and Homeland trading places on television. These two shows featured pulsing narratives fueled by post-9/11 paranoia with tales of clandestine operations at home and abroad thwarting the most sinister of foreign-backed plots. Meanwhile, the Obama administration was fighting uphill to keep the public's fervor for remaining in the Middle East alive, and our film and television industry was attempting to do the same. It was also around this time most of us just leaving high-school were finally able to gaze upon the effects of the 2008 financial crisis and recognize the public's palpable lack of faith in our national institutions. When The Crazies hit theaters, it was still a reminder of the extraordinary capabilities of the US military to swiftly contain a severe threat, but not in the way many expected who were not already familiar with Romero's original film.

The Crazies remake features a promotional poster with the tagline "FEAR THY NEIGHBOR" and stars Timothy Olyphant as David Dutten, the sheriff of the fictional town of Ogden Marsh set in rural Iowa. The film opens at a picturesque afternoon high school baseball game attended by the sheriff and a good portion of the town's population. A man named Rory is seen in the distance stumbling into the outfield in a state of confusion wielding a shotgun. David cautiously confronts the man he's familiar with, noting that this is just a drunken episode, but is forced to shoot him dead when Rory motions with the shotgun. Later, David's genuine apology to Rory's widow is rejected, and the town is now on the cusp of a nightmare that begins with a fracture of trust in their primary institution of authority.

The film's opening of a close-knit community sheriff losing the trust of his neighbors is just the beginning. David and his deputy, Russell, follow up on a claim about the corpse of a pilot being found in the nearby swamp, which reveals a large submerged military aircraft. David urges the mayor to shut off the town's water supply, fearing contamination, but the mayor refuses. David's wife, Judy, the town's doctor, treats a man exhibiting similar odd behavior, and releases him with a recommendation for further examination. That night, that same man locks his wife and son in their upstairs closet, and burns down his own home with the two trapped inside. At the morgue, David is attacked by a rabid pathologist armed with an electric saw, but is rescued by Russell. Not long after, David, Judy, and Russell are captured by a military unit.

After being swept up in the chaos with the other resident's of Ogden Marsh, they find themselves herded into a rushed medical examination and separated by the military which established quarantine protocols at the local high school. After managing to escape and rescue Judy when the fire team rams a fence releasing a large group of captured civilians, they are on the run from both infected rabid townsfolk, and the military containment unit occupying Ogden Marsh. When David manages to capture a frightened young solider, David gets him to reveal that their only orders were to contain the town's residents, but admits he did not want to continue to kill unarmed civilians. The young and frightened solider lets them escape, revealing the military's loose grasp on its own efforts to contain the outbreak.

It is worth noting that, unlike Romero's film, which still reads as directly influenced from the horrors of the Vietnam War, Eisner's remake is unmistakably right-wing coded, albeit more doomsday prepper libertarian fantasy than authoritarian power trip fantasy. The plot drives right into the Fox News FEMA narrative - a right wing conspiracy theory that claims FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) will round up and imprison American citizens in concentration camps after a state of national emergency has been declared. Glenn Beck, Alex Jones, and U.S. Rep. Michele Bachmann have pushed theories of government concentration camps on US soil. This conspiracy theory is often trotted out every so often to incite their base's fears of the overarching New World Order conspiracy theory, which has been rolled into QAnon in recent years as an ever-flowing conspiracy which all the affiliated media pundits and grifters are still working out the details of.

The conservative dilemma presents itself in this remake as the protagonists learn that their authority and status in their own communities can be easily erased by the state at large, if and as needed. The film addresses a concern of what real liberty looks like, and how Americans deal with the often defeating reality of vertical power structures. If our small towns have noble and trusted community leaders that can be round up in the same flock as regular citizens by a larger and national governing body to be eradicated, of what use are these power structures that we cling to for protection? This is the root of a large portion of right wing doomsday fantasy, in which the delusion of grandeur for the part of the second amendment in which the individual or well-regulated militia combats the tyranny of the US government and prevails. However, both the remake and the original film's protagonists going up against infected townsfolk and the government suggest deeper tears in the fabric of small town America.

Eisner's The Crazies really wastes no time setting up and tearing down an idyllic day in small town Iowa. David having to shoot and kill a member of his own community in front of the entire town, while standing on the very field that host's America's past time, reveals that our idealized American reality is always at risk of fracturing. After David and Russell discover that their communication to the outside world has been cut, David runs outside to look for help. The only person seemingly left in town that he sees is a middle-aged woman singing to herself in a daze, possibly infected. She is shown wearing a blue dress and riding an older bike, all seemingly from the 1950s. This woman is never named, but is the last resident David witnesses before he spots a black SUV speed off after photographing him from a distance. In this quick scene, Eisner shows us a woman adorned in the aesthetics of an idealized American past, and uses her to distract David as he is being surveilled.

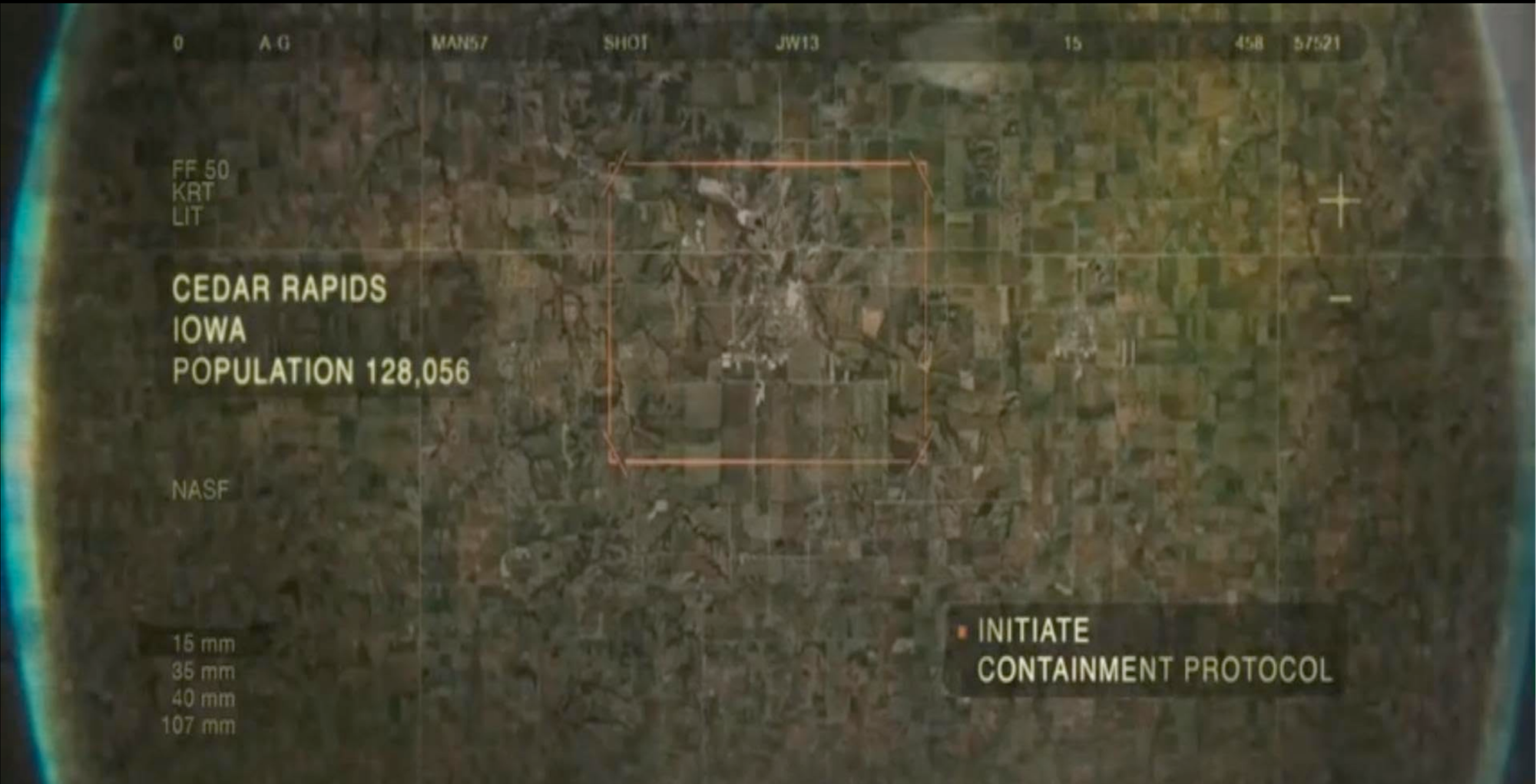

After desperately trying to make it out of town and narrowly escaping death, they intercept a black SUV driven by an intelligence official representing the containment task force. Responding to the situation they find themselves in as a catastrophic fuck-up, the official reveals that the plane was carrying a rhabdoviridae prototype bioweapon codenamed "Trixie". He mentioned that this prototype would one day be used to destabilize entire populations, but it just destabilized the wrong population. Later, David and Judy discover that the evacuees escorted out of town were executed, and that the military plans to detonate a large bomb to destroy what's left of Ogden Marsh. After narrowly escaping to a major highway headed for Cedar Rapids, a satellite identifies and targets the sole survivors, before marking Cedar Rapids as the next target of their containment efforts.

2010's The Crazies trades some aspects of Romero's original rabid pace and tone for a sleeker and distilled take that managed to surprise audiences by harnessing the political subtext of the original story and still deliver a solid outbreak thriller. Both films demonstrate that those with the power have made it clear that our shared desire to maintain safety and integrity in our own communities, and on our own terms, is secondary to their hegemonic order, which must be maintained domestically and internationally. The Crazies is a horror movie that tricks the audience into thinking that the protagonists are heroes of the law with any power whatsoever. Many shots in the film allow the audience to see past a subject to the horizon beyond the crop field, implying that the idyllic isolation that many Americans imbue with a romantic sense of simplified patriotism is still inextricably linked to a larger idea of government that may have a different idea of maintaining peace outside of relying on a noble sheriff.

Eisner's remake is never once positioning itself to be better than Romero's original film, but it does manage to slow its roll and use its more even pacing to focus on Romero's Vietnam-era politics and show how they have been morphed by contemporary conspiracy theories and right wing fantasy. At the heart of both stories is still the small town setting, and our idea of maintaining a civil society within larger systems of power. It can be hard to face a reality wherein our man-made power structures look like a food chain diagram in a kid's science book. In the scene in which David is demanding answers from the captured intelligence officer, his rage is palpable. The higher ranked intelligence officer mocks, "Look fella, we lost a plane. What do you want me to say?" To him, the extermination of the population of a quiet small town in the American Midwest to cover up the possession of a bioweapon prototype is a workplace mishap, like spilling coffee in the printer.